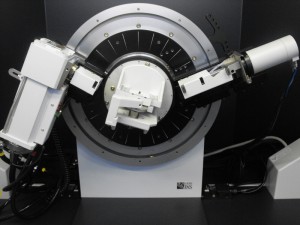

All of the powder XRD (PXRD) systems we work with use either manually interchangeable aperture slits or automatic (stepper motor driven) slits to control divergence and scatter. One of the most common questions I hear from new users is “What is the ideal slit arrangement”. While I realize that there are many instruments out there with “one-size fits all” slits, the D500, D5000, D5005 and D8 optics are what I call “Research Grade”. This means that they can be adjusted and tuned for a particular application to maximize effects that are desirable and minimize those which are not. One of the most common reasons to change the anti-scatter and divergence slits is to reduce scatter over the sample at low angles. This scatter is the primary limiting factor for users who want to see diffracted peaks at very low angles. At Texray, we offer instrument time (data collection) as one of our services and have received requests for starting angles as low as 1 degree 2theta so it occurred to me that now would be a good time to collect some reference data and answer this question once and for all.

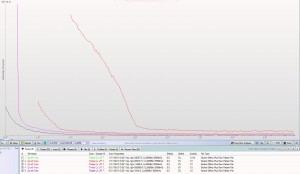

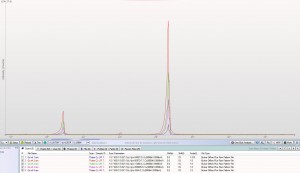

The image on the left shows the effect that the anti-scatter and divergence slits have on low angle scatter. The image on the right is of the two primary reflections of quartz (Novaculite) with the same slits. Note the intensity loss. The benefit of automatic slits is that they can be set very small at the beginning of the scan and gradually open up throughout the angular range. Very few users need that kind of flexibility, but since we’re talking about slits, it bears mentioning.

This data was collected with matched slits set at 0.2mm, 0.6mm, 1mm and 2mm. These correspond to practical starting angles of 0.6, 0.9, 1.4 and 2.5 degrees 2theta respectively.

Looking at the actual peaks, you can see the affect the smaller slits have on the rest of the data. These were collected without the benefit of a diffracted beam monochromator and with the primary soller slit removed. Neither of these factors would have a dramatic impact on the result, but the lack of a primary beam soller slit explains the asymmetrical peak shape in the second scan range pictured.